Little details

On my (practice) painting paper I paint a few leaves and fruits, bigger than life size, then life size. This helps me to get the colours right, and to select the best approach for applying the paint. For example I could use a series of colour washes, (wet in wet) or dry brush technique. This plant has few large areas, so washes are of limited use. For some of the detail I use the fine brush (Winsor and Newton Series 7 sable000) like a pencil.

Measured drawing

I draw a frame for my picture, using a 2H pencil. I mark out important landmarks, such as the highest, lowest and widest points on architect’s tracing paper. This paper is robust enough to withstand repeated erasures, but thin enough to allow me to trace through it.

I draw the plant as accurately as I can within the limits of the composition. As the leaves and branches are fairly congested, I sometimes put a piece of paper between the branches, in order to see the plant’s structure more clearly, and I omit some of the leaves and tiny branches, endeavouring meanwhile not to loose track of the structure of the plant. Because of the plant’s congested nature I have to pay particular attention to connections, rather than obscuring it by too many overlapping details, so that the viewer will understand the structure.

Transferring the drawing

I can use either a light box (or window lit from outside) or reverse tracing to transfer the image to my paper. Reverse tracing involves going over my drawing on the reverse side, using a 2B pencil. It is quite hard to make sure all the details are included. When I am satisfied I place the tracing paper on top of my painting paper (Arches 300gsm smooth) right side up and trace it again, using a 2H pencil to transfer the image onto the plain paper beneath. Then I have to go over the drawing carefully, with a 2H pencil, to make sure the details are preserved. The tracing process tends to blur some of the connections and details, so I sharpen them up.

Colour mixing

Before I can put colour on my painting I need to mix enough of the main colours (various shades of greyish green and brown). I do this by checking with my colour patches, the original specimens having dried out and changed colour by this time.

Painting

Now starts the hardest part. It is hard because mistakes are difficult to correct, and keeping the page clean is a challenge. It is best to test each dab of colour on a practice sheet before putting it on the paper. A slight difference in the proportions of pigment and water can make a huge difference on the page. If it is too dark, correction is difficult.

I use tiny 000 brushes for the twigs, slightly larger for the leaves. I love to see the coloured image emerge from the paper. But it is hard to slow down and paint thoughtfully, carefully, slowly, systematically. Despite the concentration required, I find it satisfying when I can find the right balance between concentration and tension. I haven’t yet given serious thought to the problem of getting the glistening texture of the plant right. For the present it is enough to paint the twigs and branches.

This part of the process is the most time-consuming. I have particular difficulty getting enough contrast between the light and darker sides of each part of the plant, not least on the branches. Getting the appearance of solidity by placing the highlight, shade and reflected light in the right spots is not intuitive for me. I have to work it out by following rules, rather than being able to paint what I see. My first attempts are not very good but can be improved. Painting stems that are three dimensional and very small is quite hard.

|

| Painting in progress (Photo copyright: Roslyn Glow, 2015) |

Perhaps my tiny brushes are too soft. I buy a few new brushes, in the smallest sizes. Like most artists I am always keen to hear of a better brush, or new watercolours.

Getting enough variation of light and shade in the leaves is a similar problem to getting form into the stems. I don’t worry too much about this at first, as I can add darker colour later, but with so many tiny leaves I know it will take some time before I am happy with it.

When I have given a preliminary coat of paint to all the branches and leaves I turn my attention to the addition of enlarged details. I go through the same process as before, composing and drawing. I decide to include the fruit and the male flower at four times their natural size. When I have completed the drawings on tracing paper, I try out different positions on the main painting. It is unfortunate that I don’t have a female flower. The fruit and male flower will have to suffice.

Since I placed the female plant to the left of the male, I follow the same sequence, placing the fruit to the left of the male flower. This is unconventional, the usual sequence being male flower, female flower, fruit, but it seems to be neater to have the details in the same order in as the main depiction. With forethought, I could have ordered the two plants more conventionally male on the left, female on the right.

Adding the magnified details

I trace the two details onto the main painting and paint them as before

Depicting the salt crystals on the enlarged details

I consult Margaret Holloway about this problem. She encourages me to try as many approaches as I can think of. The main contenders are the luminescent range of water-colours by Daniel Smith, and Windsor and Newton’s Iridescent Medium. I try numerous combinations of Daniel Smith’s colours, with names like Pearlescent Shimmer, Interference Silver, Iridescent Jade and Duochrome Green Pearl. I am grateful for the fact that Daniel Smith provides ‘Try-out sheets’, so that one can experiment with numerous colours before buying. The particles in the Daniel Smith colours seem too small for the effect I am reaching for. I try the Windsor and Newton Iridescent medium and settle for it. The resemblance to the magnified look of the plant parts is not close. My depiction looks flat whereas the crystals look quite three dimensional under the binocular microscope. It is the best I can manage.

Finishing the painting

I return to the full painting, concentrating on increasing the contrast between light and dark areas, and adding details such as the red tinge on the edges of the bigger leaves.

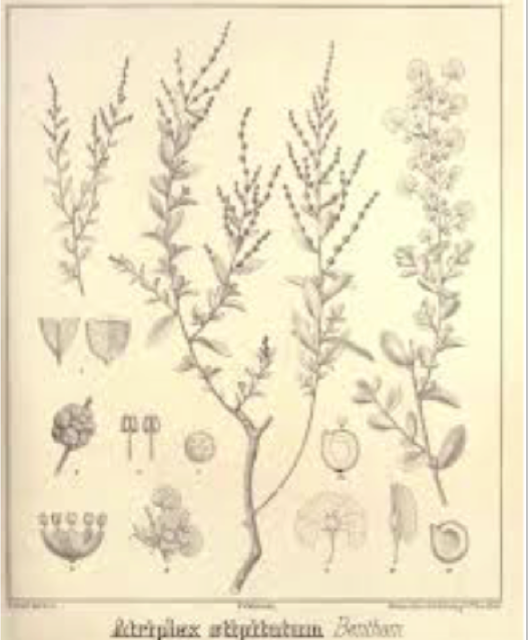

|

| The finished painting of Atripex stipitata (Photo and image copyright: Roslyn Glow, 2015) |

I am happy with the result. My modest plant has taken on a more important look when subjected to such scrutiny and attention to detail.

References

Cunningham, GM, Mulham, W E, Milthorpe, P L and Leigh, J H Plants of Western New South Wales CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Victoria, 1992, 2013. Pp 242, 244-5.

Landon, Carolyn Banksia Lady: Celia Rosser, Botanical Artist Monash Univeristy Publishing, Clayton, Victoria. See especially Chapter 9: The Painting